The icy crust surrounding Saturn’s moon Enceladus has long fascinated and intrigued astronomers. Recently, the moon revealed another part of its mysteries, which may indicate the presence of life.

Evidence collected by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft of NASA and the European Space Agency suggests that the huge subterranean ocean potentially harbors microorganisms very similar to those found here on Earth.

The hypothesis is from a new study published in the journal Nature Astronomy conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Arizona and Paris Science & Lettres University. From readings from Cassini, the researchers found that Enceladus is spewing methane gas along with the plumes of water erupting from its crust.

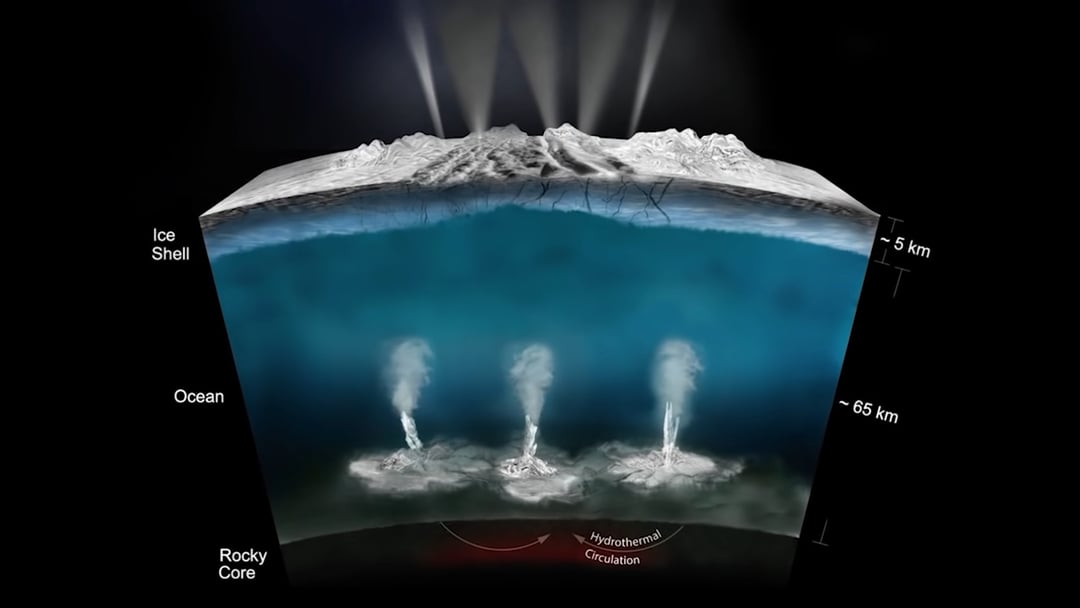

The giant plumes of water erupting on Enceladus have long inspired research and speculation about the vast ocean believed to be sandwiched between the moon’s rocky core and its frozen crust. By sampling the substances spewed out in the plumes and analyzing their chemical composition, Cassini detected a relatively high concentration of molecules normally associated with hydrothermal vents found at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, specifically hydrogen dioxide, methane gas, and carbon dioxide. The amount of methane found in the plumes was particularly unexpected.

According to the study, the amounts of methane gas found suggest that the moon’s underground oceans may be habitable for microorganisms that feed on the hydrogen released from hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor.

The hypothesis is based on Earth’s hydrothermal activity. On Earth, this activity is caused when cold surface water flows down to the bottom of the ocean, where it is heated by local heat sources, such as magma. This water is then expelled through vents in the ocean floor, releasing hydrogen and carbon dioxides.

From these two substances, microorganisms take advantage of the chemical imbalance in the water as an energy source, producing methane from carbon dioxide in a process called methanogenesis.

But proving this hypothesis is far from an easy task. Detecting whether methanogenic microorganisms are responsible for the amount of methane present in the plumes of Enceladus would require deep-diving missions into the moon’s oceans. Something that is not very close to happening.

The research team then built mathematical models to see if methanogenesis could explain the data collected by Cassini. The conclusion: the Cassini data is consistent with microbial activity from the hydrothermal source.

Microbes on Saturn’s moon?

The results suggest that even the highest possible estimate of abiotic methane production – without the involvement of living organisms – based on known hydrothermal chemistry is far from sufficient to explain the concentration of the gas measured in the plumes. Adding biological methanogenesis – done by living organisms – to the mix would coincide with Cassini’s observations.

But this does not mean that the presence of life outside the earth has been proven. Only that one possible explanation for the abundance of methane on Saturn’s moon is the presence of microorganisms.

The researchers have not ruled out that other possible abiotic processes, different from what we know, could explain the methane data. For example, the chemical decomposition of primordial organic matter in the moon’s core could be causing the ejection of significant amounts of methane.

Obviously, we are not concluding that life exists in Enceladus’ ocean,” says Regis Ferriere, associate professor at the University of Arizona and lead author of the study. “Instead, we wanted to understand how likely it would be that the hydrothermal vents on Enceladus could be inhabited by Earth-like microorganisms.”

If we consider that the probability of life on the moon is extremely low, alternative abiotic mechanisms become much more likely, even if they are very strange compared to what we know here on Earth, explains the researcher.

At the moment, scientists simply do not have enough data for any conclusions. But it’s enough to excite the scientific community and raise expectations for future missions that allow first-hand analysis of the moon.

Related posts: